Dear Reader, I hope you enjoy this article. -Vitaliy

If you love it, share it with your friends, enemies, and perfect strangers. (they can subscribe here).

Thank you to everyone who donated to Tikva Odessa, a charity in Ukraine that helps Jewish orphans. With your help, we raised $17,518.

You can listen to a professional narration of this article below:

Article available in Spanish here.

February 2022

Four times a year I write a letter to IMA clients. These letters are long; the most recent Fall letter is 27 pages. I try very hard to bring IMA clients into our thinking about the economy, investing, stocks and decisions we’ve made in their portfolio (in this essay I explain the reason for their length.)

I believe the relationship with my readers has evolved over the years such that we don’t need to sanitize and rewrite these excerpts into essays: Over the next few months, I’ll share with you excerpts (You can read the other parts here) from the Fall letter.

I’ll leave them in the raw, original, more honest form. Enjoy!

See More Clearly With These Two Mental Models

I am a big fan of mental models. Mental models are explanations of how things work. They allow you to think through analogy, often folding complex concepts into simple ones and transporting them from one discipline to another. Mental models are thinking shortcuts. I am wired to think through mental models – my brain doesn’t handle complex well and constantly tries to simplify things. If you arm yourself with mental models, you’ll often see what others don’t.

Another beauty of mental models is that you can combine them. I am about to share with you two mental models. I used both in our seasonal letter to explain one of the companies we bought for our portfolio. I am going to stop short of sharing our analysis of the company or its name. It is a small, $600-million market cap company, and I don’t want my writeup to influence its stock price. But I really hope you find value in these two mental models.

Myopic circles

I don’t smoke. This was not always the case with me. I smoked in my teens. I quit when I was 21. I was one of the first people in my circle of friends to quit smoking, then gradually all my friends quit smoking, too.

Today I don’t have a single close friend who smokes. I didn’t look for this outcome intentionally; I didn’t stop being friends with smokers. Nor do I choose friends based on their (harmless, at least to me) vices. So this was not a conscious or even a subconscious decision. Very simply, people in my social demographic circles have a set of values, and a healthy lifestyle is one of them. It’s very hard to have a healthy lifestyle and smoke.

Humans are tribal, and we try to conform to the values and behavior of our tribe. At some point in the late 1990s or early 2000s smoking stopped being cool and became uncool in my tribe. (For me, a girl I was dating was the impetus for my quitting).

On the other hand, I have a relative who smokes. This is where it gets interesting. He has a few dozen friends who smoke. His friends know a lot of people who smoke. The overlap between his circles of friends and acquaintances and mine is very small (near zero).

Why is this important? In my daily life I encounter very few people who smoke, and thus it is easy (if I am not careful) to form a belief that nobody smokes. When we started doing research on tobacco stocks, I was shocked to discover that 35 million Americans – 14% of the adult population – still smoke. The numbers are much greater in Asia and Eastern Europe.

Another example: vaccinations. If you are vaccinated, then it’s likely that most of the people you know are vaccinated. Now, if you have a friend or a relative who is not vaccinated (other than for a unique medical reason), most likely that person knows a lot more unvaccinated people than you do. And his/her circle of unvaccinated friends and your circle of friends have little overlap.

This myopic circle framework applies to many parts of our lives. Here are more examples: What we watch on TV is influenced by our values and our willingness to share our experience with others; how we watch TV – over the internet or over cable; our political beliefs – we tend to surround ourselves with people we agree with; our shopping habits (our preferences for shopping at malls, on QVC, or online); even the type of cars we drive (electric vs ICE).

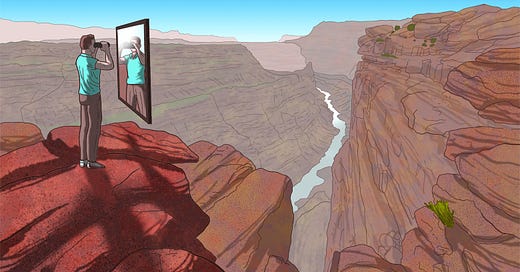

When we live in our micro circle we forget about the existence of other circles. If we are not careful, the lens through which we look at the world may get strongly tinted with our perspective and turn myopic.

You’d think that as you venture out on the world wide web this would change. It does a little, but not much. Maybe a guy you went to third grade with, who is now your Facebook “friend,” has different political views from yours. You argue with him over the occupant of the White House and then de-friend or unfollow him. But mainly, your social networks will feed you content that agrees with your biases.

For an analyst (and, I’d argue, for a human being, too) myopic vision is dangerous. It leads to missing both opportunities and potential threats.

David vs. Goliath

A book that has had a profound impact on me not just as an investor but as a businessperson is Malcom Gladwell’s David and Goliath. It reexamines one of the oldest biblical stories. Three thousand years ago in the Elah Valley of the Judean Mountains, an army of Philistines and an army of Israelites, led by King Saul, faced each other.

The armies were stalemated. To attack, either army would have to go down into the valley and then climb up the enemy’s ridge. The Philistines ran out of patience first and sent their greatest warrior, Goliath, to resolve the deadlock in one-on-one combat. Goliath was a 6-foot 9-inch giant, protected from head to toe by body armor and a bronze helmet.

He yelled, “Choose you a man and let him come down to me! If he prevails in battle against me and strike me down, we shall be slaves to you. But if I prevail and strike him down, you will be slaves to us and serve us.”

There were no volunteers in the Israelites’ camp. Who could win a fight against this giant? Then an ordinary-looking shepherd boy stepped forward. His name was David.

To me, David vs. Goliath was always just an inspirational story about a young boy defeating an evil giant. Or as Gladwell puts it, for most people David vs. Goliath is a story of “when ordinary people confront giants.”

But Gladwell presents the story in a very different light. When David goes to face Goliath, King Saul offers him his sword. David refuses. Instead, he picks up a few polished stones and throws them in his pouch. Gladwell explains that, as a shepherd protecting his flock, David was a skilled rock slinger.

When Goliath saw David, he yelled something along the lines of “Come here; I’ll have a piece of you!” Instead, David kept his distance, then put a stone in the leather pouch of his sling, fired it at Goliath’s exposed forehead, and struck him down.

Had David taken Saul’s sword and gone to fight one-on-one, he wouldn’t have had a chance. But where everyone saw strength in Goliath’s physical might, David saw weakness. David was a craftsman rock slinger; he could knock a bird down in mid-flight with a stone – Goliath was a sitting duck.

Suddenly we see a very different story. Goliath’s size, physical strength and armor are only competitive advantages if his opponent chooses to fight him in a conventional way, on Goliath’s terms. But his strength can quickly be turned into serious weakness, as Goliath was immobile, slow and had no defense against a skillful rock slinger. In other words, Goliath brought a sword to a gunfight. Or in financial parlance, David turned Goliath’s assets into liabilities.

I keep this framework in the back of my mind when I run IMA – the investment industry is full of Goliaths. Twenty years ago they would have had a competitive advantage over IMA – they would have had access to better tools and more information (before Regulation FD management would have whispered in their ear information it would not share with the public.) The internet and new regulations have changed all that. We don’t have a large research department staffed with twenty analysts. Thank God!

We don’t have the bureaucracy or the politics that comes with that sort of department. We chose to compete with Goliaths on our terms – we deliberately created a large network of investors we respect. We share our ideas with them, and in exchange they do the same. It’s a two-way street. We have our industry or country experts to whom we reach out when we need to get constructive feedback on the idea we are pursuing. We even organize a conference, VALUEx Vail, open only to our network to foster this exchange. Large firms are also constrained by their size – we are not; we can buy a company of almost any size in the US or overseas. If our size becomes a constraint for us, we’ll put the brakes on our growth.

The lesson of this story is to always look for asymmetry. When you face a formidable competitor, don’t settle for symmetrical one-on-one combat; understand the competitor’s strengths and see if you can turn them into weaknesses by changing the domain of the fight.

Aida

This is a continuation of my journey into musicals (previous musicals).

In this exploratory journey of musicals we’ll briefly venture into the adjacent world of opera, as I’ll discuss both Aida the opera and Aida the musical, both based on the same story.

Let’s start with the opera. Aida was composed by Giuseppe Verdi and premiered in Cairo in 1871. It was commissioned by the ruler of Egypt to celebrate the opening of the Khedivial (Royal) Opera House in Cairo. The original Aida came with a five-minute prelude. A prelude is short piece of orchestral music that sets the mood for the music to come. Preludes are usually played before an act of the opera – not at the beginning of the opera. Overtures are usually longer pieces that are played before the opera, as their job to expose the most important motives of what you are about to hear. Before a performance in Milan in 1872, Verdi composed an 11-minute overture for Aida, which he then decided not to use. To this day most performances include the prelude, not the overture. You can listen to Aida’s overture, which is terrific, here.

Today, 150 years later Verdi’s Aida is still one of the most-performed operas.

Aida’s story takes place in Egypt, which is at war with Ethiopia. Aida is an Ethiopian princess captured by the Egyptians and serves as a slave to the Egyptian princess Amneris. Amneris is in love with the young Egyptian general Radames, who is leading the war against Ethiopia. What complicates this picture is that Radames is in love with Amneris’s servant Aida, and Aida is in love with him. To quote from Aida the musical, “Every story is a love story.” The story here is not your typical love triangle, it is a more like a love square where love for country is thrown into the mix: Radames has to make a choice between Aida, Amneris, and Egypt. You’ll have to watch the opera or the musical to find out how this dramatic story unfolds. (You can watch a summary of the opera here).

Now let’s move on to Aida the musical.

Aida was a continuation of the relationship between Disney and Sir Elton John (music) and Tim Rice (lyrics) after their previous successful collaborative effort on the Lion King musical. The Aida musical had a rough start. Its first production, in Atlanta, suffered a malfunction of a complicated $10 million pyramid contraption. I read a story somewhere that the malfunction was the best thing that happened to the production. As it broke, all the performers came out on stage and started to sing their roles as if it were not a staged musical but a concert. The audience did not care; they loved it. Aida’s producers knew they had a successful musical – a great combination of terrific music and a powerful love story – and that it didn’t need overcomplicated contraptions and super-fancy sets.

I love Heather Headley’s singing of Aida, and here is my favorite recording of her singing Aida’s main song, “Written in the Stars”:

Here is my latest Youtube video:

Vitaliy Katsenelson is the CEO at IMA, a value investing firm in Denver. He has written two books on investing, which were published by John Wiley & Sons and have been translated into eight languages. Soul in the Game: The Art of a Meaningful Life (Harriman House, 2022) is his first non-investing book. You can get unpublished bonus chapters by forwarding your purchase receipt to bonus@soulinthegame.net.

Please read the following important disclosure here.