My brother Alex, my son Jonah, and I are going on what has become our annual trip to Switzerland to attend my friend Guy Spier’s investment conference, VALUEx Klosters. Before the conference, we’ll meet with the management of one of our companies in Geneva and then embark on a horological journey through Switzerland. We’re going to drive from Geneva to Zurich and visit half a dozen small watchmakers in the Vallée de Joux (most of them make fewer than a thousand watches a year).

In 2025, I finally got bit by the mechanical watch bug. Alex and Jonah are fanatics. I resisted for years—my view was that watches are useless trinkets. But the more I studied the retailer, Watches of Switzerland (one of our holdings), the more I appreciated the tension between art and craft in watchmaking. In a world of $15 quartz watches, mechanical timepieces don’t exist to tell time—they’re our last grasp at analog craftsmanship.

For me, it’s not about collecting—the possession of watches. I don’t have to own Monet’s paintings to admire them. But unlike with Monet, I can actually talk to these artisans, and there’s a lot I can learn from them.

--

The 15th annual Intellectual Investor Conference (formerly known as VALUEx Vail) will be held June 24-26. If you’re a die-hard value investor, you can apply here.

--

This is Part Two of my interview with CFA Society UK in London. In Part One, we discussed investing with intention, how to define risk properly, and how to build a disciplined investment process that endures over time.

In Part Two, the conversation shifts to artificial intelligence and its impact on investing. We explore what is structurally changing in the AI landscape, what may be cyclical or speculative, and how long-term investors can think clearly when market excitement is high and uncertainty is even higher. You can read the whole transcript here.

Artificial Intelligence, Nvidia, and the Risk of Overinvestment - Part 2

On Intangibles and AI in Investing

A large portion of business value today comes from intangibles rather than hard assets. What do you think about that, and how are you navigating AI?

I’m going to answer two questions—the one you asked and the one I want to answer.

First, on AI: If you embrace it, AI can make you smarter. If you look at AI as a tool, it becomes your friend. If you outsource your thinking to AI, it can make you dumber.

Thirty years ago, I had very good handwriting. Then personal computers came, I started typing, and today I can barely write by hand. That skill atrophied.

Today I see people outsourcing writing to AI. It worries me, especially for my kids—they’re going to forget how to write. That’s a huge negative.

But AI can also be your sparring partner. You can debate a stock with ChatGPT, and that makes you smarter. It helped me edit my book—usually you send a draft to an editor and get it back two days later. Now I can have an editing process in real time. I’m still doing the writing; AI is helping me edit.

We use AI in our research process, but carefully. We don’t want AI thinking for us—we want AI helping us think.

Here’s an example: I still read or listen to conference calls. But say I’m looking at a company for the first time and want to understand what happened over the last ten years. We download transcripts of earnings calls, throw them into ChatGPT, and say, “Tell me how management’s narrative has changed over the years.” I get a page-and-a-half summary. Before, that would have taken me a week reading 500 pages. Now I have new data that wasn’t accessible before.

Another example: A company claimed their prices were much cheaper than competitors’. I asked ChatGPT to compare their prices to every competitor, and it actually went to websites, navigated menus, and selected options. Twenty minutes later, I had a table listing all the prices.

On intangibles: Yes, the economy has changed. We’re becoming more of a knowledge economy. And the scary part is the speed of change. I look at Google and have no idea what its future looks like. I have friends who are very bullish on Google—they have good reasons. Google has TPU, their own processor, much cheaper than Nvidia. They came out with Gemini, which is supposedly phenomenal.

But three years ago, nobody questioned whether Google Search would remain a monopoly. Today it has competition that wasn’t there before.

A lot of times I look at these things and don’t have an answer. I wrote an article about this: Today everyone feels they have to have an opinion on every Magnificent Seven stock. I look at them and really don’t know—and by the way, a lot of them aren’t cheap.

But here’s what’s liberating: I have a portfolio of 25, maybe 30 stocks. There are 10,000 stocks out there. I don’t have to own Magnificent Seven stocks. I just need 25, and I have 10,000 to choose from.

So I can look at a company and ask: Is AI going to change this business? Benefit it? If I have no idea, I just move on to the next stock.

Is There an AI Bubble?

Now I’ll answer the question I’ve been waiting for. I expected it five questions ago. Is there an AI bubble?

I’ve thought a lot about this. I break it into a few parts.

From a stock perspective: look at Nvidia. Its income statement looks like a software company’s—maybe 75% gross margins (for context, Microsoft’s gross margins are 69%, Salesforce’s 78%).

Another data point: Intel at its peak dominance, when it was king of the world, when every computer and server ran on its chips, had max pretax margins of 32%—and only for a few years. Nvidia’s pretax margin today is 62%.

This is because Nvidia is essentially the only company making GPUs, outside of AMD and a few from Google. So they can charge incredibly high prices.

The problem is there are startups working on competing products. And then you have Google, Meta, Tesla—all the companies paying Nvidia billions—working on their own chips.

If capitalism works, Nvidia won’t be the only GPU provider forever.

Bulls will tell you that Nvidia trades at “only” 30 times earnings.

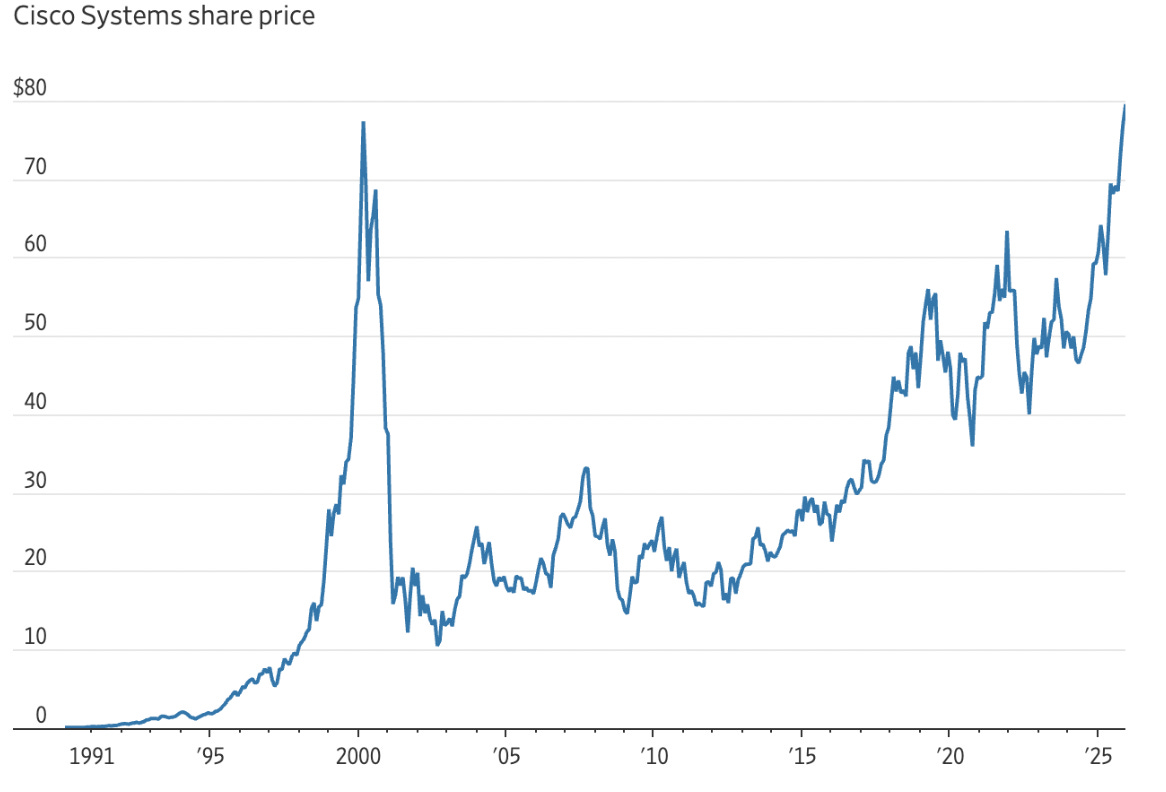

I remember, when the telecom bubble was bursting, reading bullish articles arguing that Cisco was trading at “only” 30 times earnings. If you bought Cisco then, at “only” 30 times forward earnings—and those earnings estimates were based on pie-in-the-sky projections—it took you literally a quarter of a century, a generation, to make your money back.

Nvidia’s stock is likely going to follow a similar path.

But I don’t want to talk about earnings.

The value of any asset is the present value of future cash flows over a long period. If you buy Nvidia today, you have to be certain those cash flows are sustainable. I’d question that.

Let me tell you what’s priced into Nvidia today. I ran a discounted cash flow model: revenues doubling to $400 billion by 2027 and then growing 7% a year for 17 years, margins remaining at current levels, and cash flows discounted back at 7% a year. If you’re comfortable with these assumptions, you’ll make 7% a year—the discount rate.

But that’s actually the least interesting part. Here’s what gets interesting: Half of US economic growth over the last couple of quarters came from data centers. The rest of the economy is probably shrinking—or at best not growing. Take data centers away, and what do you have?

We probably have an overinvestment bubble. That’s where the bubble is happening.

I read today that DeepSeek, the Chinese version of ChatGPT, can generate tokens at 95% lower cost—some insane number. In my new book, I talk about the power of constraints. When you don’t have financial resources, when you don’t have Nvidia GPUs coming freely, you have to become more creative. You have to create more efficient models. That’s what DeepSeek did.

What’s happening today in AI infrastructure looks very similar to the 1998–1999 fiber optics overbuilding. Remember Global Crossing, Level 3, Qwest, JDS Uniphase, WorldCom? Those companies were at the center of fiber optics, investing insane amounts of money because people said internet demand would be huge and insatiable.

They were right—demand was huge and insatiable. But guess what? Most of those companies either went bankrupt or nearly did. Equity holders got wiped out. Bond holders lost nearly everything.

Why? When everybody invests at once, you get overcapacity. Mark Zuckerberg said it doesn’t matter if Meta overspends a hundred billion dollars—the threat of not doing it is existential. But if Google, Tesla, and Meta all do the same, and everyone does the same, you get overcapacity. Most of these investments become malinvestments.

Also, technology changes. Part of why we have so much dark fiber 25 years later is that Cisco figured out how to compress data. You need less fiber. DeepSeek-type innovations will likely make AI training more efficient, so you won’t need as much compute.

And consider this: The internet was huge, but growth went exponential in 2008 with the iPhone, putting the internet in everyone’s hands. For AI, robotics might become that moment. But my point is: The road to AI won’t be linear. It will have a lot of bumps.

But that’s not what worries me most. Here’s what worries me:

I read about Meta’s data center in Louisiana—$26 billion cost. You won’t find that $26 billion as a liability on Facebook’s balance sheet. They created a special purpose entity, put in a few billion, and it became someone else’s problem.

There’s a debate about GPU useful life—some say two years, some say three, some say six. Can we agree it’s not 24 years? Well, that data center has been financed with 24-year debt. Of that $26 billion, I promise you $20 billion or more is not concrete—it’s GPUs going to Nvidia, financed with 24-year debt. A lot of it comes from private credit.

This looks very bubbly. There’s a debt issue coming.

The pushback I get: “Usually people don’t talk about bubbles during bubbles.” That’s true. Bubbles can last much longer than you think. People like me will get sick of talking about it, and that’s when it ends in tears.

Oracle changed the AI race from being financed by cash flows to being financed by debt.

Let me walk through Oracle’s numbers. Market cap: maybe $600 billion. Free cash flows: roughly $12–15 billion. Net debt: about $80–90 billion. And they just committed to spend hundreds of billions on the OpenAI deal.

Remember: $15 billion in free cash flows. A lot of debt already. And now hundreds of billions in commitments. Larry Ellison is making an all-or-nothing bet. He’s borrowing, Meta’s borrowing, everyone’s borrowing—that’s what’s happening.

I just finished reading Andrew Ross Sorkin’s book on 1929. Highly recommend it—great insight into people. One character reminded me of someone today: William C. Durant. He started General Motors, got kicked out, co-founded Chevrolet, merged it with GM, got kicked out again. A brilliant businessman who started two auto companies.

But he speculated in 1929, got wiped out, and died destitute, managing a bowling alley in the middle of nowhere.

You look at him—brilliant, very smart—and yet he still did these dumb things and got wiped out. I keep thinking about Larry Ellison. I don’t think he’ll end up managing a bowling alley on his private island in Hawaii. But—coming back to your earlier question—you want to say, “Well, if he’s smart here, he must be smart there.” I’ve found it often doesn’t work that way.

What concerns me is that this behavior can last a long time before it ends. And I’m concerned about the financial consequences for pension funds and others doing private credit with very little thinking or underwriting. I’m also concerned about the health of the overall economy once you take away AI spending.

The Future of Asset Management

How do you see the asset management industry evolving with AI and passive investing?

Believe it or not, I think passive investing is a gift to people like us who do active management. Not in the short term, but in the long term.

The more people do passive investing, the less analysis gets done. The less analysis, the more you compete against dumb money. When I say “dumb money,” I don’t mean people who buy index funds are dumb—in fact, they were smarter than many professionals. It’s just that it’s a one-directional decision: buy everything. Very little analysis goes into valuing each stock.

Long term, I’m very optimistic because I’ll have less competition. It used to be 500 people valuing a stock; now there’ll be 20.

One thing that worries me—and I have to be honest, I contribute to this problem—is that in ten years we’re probably going to kill all the young analysts.

In the past, you’d have kids graduate from school, become young analysts. You’d ask them to read transcripts, summarize them, compare prices. Now I don’t need them—AI does the job of 20 analysts. So I’m not hiring them.

But to become an analyst, you have to go through vocational training, rise up through experience. If we’re not hiring young analysts, who comes after us? I don’t have an answer. That worries me.

But investing itself—we’re going to have to embrace AI or get run over. We have almost a full-time person now just figuring out how to bring AI into our research process. Not thinking for me—helping me think better.

Everyone who works for me, in any job, I ask to embrace AI. For however old you are, you didn’t have AI to go to before. Now when you have a question, you have a very smart assistant that can help you answer it—not thinking for you, but helping you think. You have to reprogram decades of behavior. That’s very important.

La Traviata: “The youthful ardor of my ebullient spirits”

We are exploring timeless arias from Giuseppe Verdi’s opera La Traviata.

Here’s “De’ miei bollenti spiriti” (“The youthful ardor of my ebullient spirits”)

Alfredo’s joyful reflection on his new life with Violetta, a lyrical tenor aria full of optimism and tenderness.

Really appreciate this perspectve on AI overinvestment, people forget how these cycles work. Your comparison to past tech bubbles is spot on, especially when everyone's convinced this time is different. The Nvidia angle is particuarly interesting given how much weight the entire AI thesis rests on their infrastructure.